The concept of abstract art meeting philosophically intriguing writing, in the graphic novel context, has interested me for a long while, now. How timely should it be that the father and champion of what may have been a virtually new art-form has awoken from its hibernation and stricken my heart at last. Batman: Arkham Asylum, written in 1989 by Grant Morrison and illustrated by Dave McKean, is a graphic novel that was without precedent, without peer, and is arguably without contention, to this day, as the finest comic book ever published. The record it holds as the best-selling work in the industry's history certainly suggests so. Popular acclaim stands it erect in line as a classic, a class including many formidable productions of marvelous novelists and artists. In spite of the hype, perhaps, many other reviews have created, this reading was certainly no disappointment.

What Morrison and McKean concocted just about 25 years ago doesn't invite readers, then or today, to indulge the classic version of Batman and the Joker. The artists beckon an unsuspecting audience to take part in a near-claustrophobic "feast of fools", hosted by a clown in a dark house, originally intended for something nobler than dooming the sane, the moral, the rational. The novel is characterized by spellbinding imagery, and an unorthodox assortment of paintings, photography and etchings. It's rich in symbolism and purpose. The story is, just as well, harmoniously conniving and surreal. The amalgamation of this near-illusory craft creates a beautiful sum of literary work that compels even the most ordinary folk to the deepest, most necessary philosophizing.

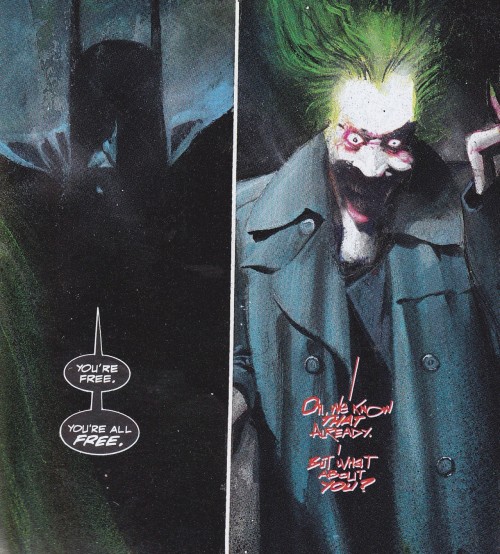

The old DC story follows the parallel paths of Amadeus Arkham, pre-world-war-two founder of the infamous Arkham Asylum, and Batman, the protector of Gotham city's innocent. The inmates of the said asylum "for the criminally insane", king-ed by the Joker, have staged a takeover and successfully seized control of the facility. Notably, this takes place on the night of April 1st, April Fool's day. The Joker's one last demand before he releases the hostages his henchmen hold is that they have their caped adversary in their captivity. Batman enters the asylum, as ransom, unbeknownst of what craze lies ahead, or whether he may stand to escape, in the end, the clutches of his heinous enemies. Or is it one enemy? While Batman ventures to the lawless playground of the unleashed rogues, the grim history of Amadeus Arkham's own trip to insanity reawakens in the unfolding horror, only to lead the masked vigilante to his darkest nightmare.

Symbolism, Imagery and the Grand Metaphor

Arkham Asylum's plot is threaded with the incredibly luxuriant fabric of the journal entries of the aforementioned founder of Arkham Asylum. The initial entry, revealed in the first few pages, details the pains of Arkham's childhood, marked with tragedy - Amadeus's father died, his mother stricken with psychosis. Right away, our unfortunate boy, then, introduces the reader to symbolism: the beetle, which his mother sickly consumed, as one of rebirth. Rebirth into what, exactly? Another world of "fathomless signs and portents ... magic and terror ... And mysterious symbols." Then we are brought back to the present, where Batman and Commissioner Jim Gordon assess a developing situation: the Joker and his gang have taken over the asylum. The Joker, enrobed by his trademark sadistic humor, orders the Batman into the "madhouse" to free the hostages. Though other options are presented by a compassionate Jim Gordon, Batman agrees to the clown's conditions. He feels compelled to. But he's afraid:

Afraid? Batman's not afraid of anything. It's me. I'm afraid. I'm afraid that the Joker may be right about me. Sometimes I... question the rationality of my actions. And I'm afraid that when I [...] walk into Arkham [...] it'll be just like coming home.From there, we are submerged back into the mind of the deceased Dr. Arkham. In fact, the whole story is a back-and-forth process that matches the tragic events of Arkham's life and career with the grotesque afflictions of the Madhouse upon Batman's mind. Parallels intentionally mark the plot progression and sees powerful themes given flesh and unforeseeable life. Numerous instances of this intense parallelism exist that are so remarkable and subtle, it's chilling. For example, when Amadeus Arkham's family is brutally murdered by a madman, he finds his daughter's head facing him from inside an otherwise innocent dollhouse. What a fantastically gruesome comparison that is drawn between the past and the present in this story - what was intended for good is abused and marred into something horrifying, like the malignity of the Joker's laughter and the hospital turned war-zone. There seems to be a fate that is repeating itself in our hero's life.

In fact, by Morrison's creative interpretation of the hero, the Dark Knight appears much more vulnerable and seemingly a lot more penetrable in this episode. He's not the morally immune, physically impressive warrior-type we've enjoyed by Christian Bale's incarnation or Jim Lee's modern comic-book impression. The weakness of Batman, the humanness of Bruce Wayne, is more obvious. When the King of Lunacy challenges the Cape-and-Cowl to a devious word association exercise, heavy philosophical rocks are overturned as a psychological burden is laid. As the Joker examines an abstract picture on a card, he sees all kind of seemingly random images. But when he inquires what Batman sees in the same picture, the next frame literally becomes an extending bat that takes up an entire page. But as this sequence continues, your confidence is overwhelmed with pathos. An inquisitive but still insightful psychotherapist, Ruth Adams, facilitates the exercise (she's innocent and good-intending, it would seem, but must go with the Joker's orders as he's the one with the gun, at this point.) She gives the first word, "Mother." Batman responds, "Pearl."

"Handle."

"Revolver."

"Gun."

"Father."

"Father?"

"Death."

"End." Batman breaks under the agonizing weight of memory, regret and remorse and orders the exercise to stop. The pain is so thick and heavy in his mind that he would later take a shard of glass and drive it through the center of his hand, perhaps as a distraction from the real pain. But even in this moment of sheer distress, we can see the early revelations of a messianic metaphor. It's hard in literature to separate pain from any analogy to Jesus Christ, but this goes beyond mere melodrama and faint self-deprecation. The mirroring of the two figures is sincere and only right. Batman accepts every one of the Joker's challenges - the Nazarene lugging reddened lumber - even as it breaks him down to the bare fibers of his person. It's about sacrificing the subjective desire of security for the reign of what's objectively true. Something deeper and more universally abounding is on the line. This is what the fight is for. But the fight, up to this point, has only begun.

Mercilessly shooting down an officer right in front of our Caped Crusader's eyes for intimidatory purposes, the Joker gives Batman an hour in the Asylum before the inmates are unchained to kill him. And here we see that Batman must push through a hefty line-up of classic and lesser-known villains to ensure his own survival: Clayface, Doctor Destiny, Mad Hatter, Zeus, Killer Croc and Two Face. Did I miss anyone? Oh, right! The Joker! Never forget that devil. Each battle, each confrontation, seems to take a greater toll on Batman's mind. The artwork seems to follow the same, near hallucinogenic trend into a chaotic bowl of mental worms and dirt.

Symbolism is prominent throughout the escalating conflict, reflecting the story's all-too-evident, psychological underpinnings. A clock is a frequent image representing the aspect of time in the story. The house is a symbol of madness or disorder. The bride's gown a symbol for innocence. And so on. Extreme blood imagery prevails as well as an appropriate dark tonality throughout. It makes for a very captivating and altogether pleasureful opportunity for exercise in literary analysis. It's almost Shakespeare-esque in how much detail went into the various devices and creative employments by the authors. In many ways, this abstract dimension is the factor separating it from all other Batman comics.

Batman as an implicit, but nearly explicit, Christological metaphor reaches his ultimate peak in the titanic, blood-bathed battle between him and Killer Croc. Giving an added epic and personal overtone to the climactic contest between beast and man, the most vital and provocative journal entry of Amadeus Arkham is lettered, woven into the most physical performance of the whole story. As Croc and Bats have at each other, and Croc plunges a spike into Batman's gut, we have a reading of Akham's disparaging journal [excerpt] :

I have been shown the path. I must follow where it leads. Like Parsifial, I must confront the unreason that threatens me. I must go alone into the Dark Tower. Without a backward glance. And face the Dragon within. I have only one fear. What if I am not strong enough to defeat it? What then? The drug takes hold. I feel small and afraid. Perhaps I've done the wrong thing. Somewhere, not far away, the dragon hauls its terrible weight through the corridors of the asylum. I am borne up on a wave of perfect terror. And the world explodes. There is nothing to hold onto. No anchor. Panic-stricken, I flee. I run blindly through the madhouse. And I cannot even pray. For I have no God.The battle rages and blood is spilled. Batman is not only the one who bears the intense psychological burden of overcoming this "unreason", but also very clearly bears the excruciating pains that no one else could take. That no one else could take and sensibly hope to overcome on their own, finite terms. His victory would take a dramatic, heart-sickening and triumphal turn as this fantastic read reaches its awesome end.

Batman is still a hero for the ages.

The Verdict

This is a novel unlike any other I've read. You read it moreso for the art which, in and of itself, contains a story within each frame. A gallery whispering sensual songs and war poems. The immaculate variety of styles and imagery, incorporating into itself the strong symbolism, allusions and metaphors of the prose, penetrates the soul today as it wriggles and scampers to know the truth of reality, be it one of total irrationality and meaninglessness or one of universal beauty and morality. A boon for the comic book industry and DC Comics, the book bears few shortcomings. These, which I would consider disappointments in spite of a terrific script, include one very debatable scene at the end after the Killer Croc battle, and a Batman that is perhaps just a little too weak for my comfort. Nevertheless, the message and thematic elements stand tall. Grant Morrison and Dave McKean pulled off an ambitious, genius work that, in large, deserves its fame. 4 out of 5!

Morrison, Grant. Batman: Arkham Asylum. 15th. ed. S.l.: D C Comics, 2005. Print.