Truly, few stories could reach the iconic level that Alan Moore's graphic novel, Batman: The Killing Joke, does. Short yet gripping, simple yet thought-provoking, straight-forward yet ambiguous, this mysterious story about the Joker's origins, illustrated magnificently by Brian Bolland, has sparked many an interest in possibly the greatest fictional villain of all time for nearly three decades now and will surely do so for decades to come.

Not only is this my first time reviewing a graphic novel, it is my first time reading one at all. I figured that if I had to start somewhere, it would have to be Alan Moore, who has written legendary, all-time greats such as V for Vandetta and Watchmen. Because of my fairly recently developed curiosity in the superhero pantheon, and, more specifically, the Batman universe, I had to read The Killing Joke. Of course, my perspective on this novel is, to me anyway, a strange one because I'm a 21st century kid, having already experienced the splendor and modern-age brawn of Christopher Nolan's record-breaking Batman trilogy, and now suddenly reading a more classic Batman story released originally in 1988. Normally, one starts with the classic story and then graduates to the new stuff. Normally one reads the book before they watch the movie. In this sense, I feel a bit spoiled. In fact, I almost feel as if I've been robbed of being able to fully appreciate this story. Nowadays, however, young people seem to be able to forgive themselves for committing this sort of cheating, so I'm sure no one is going to illegitimize my opinion for it. On the other hand, though, Batman's story - the Joker's story - is one that's evolved into many variations, rather than having a single, true version. In the afterword of the 2008-released, newly colored deluxe version of The Killing Joke, Brian Bolland admits his original hesitancy to jump on board with the story Moore created as the Joker character has so many different versions of his beginnings and personal stumbling into craze. With this being considered, perhaps I haven't really cheated at all, having watched the Nolan trilogy first.

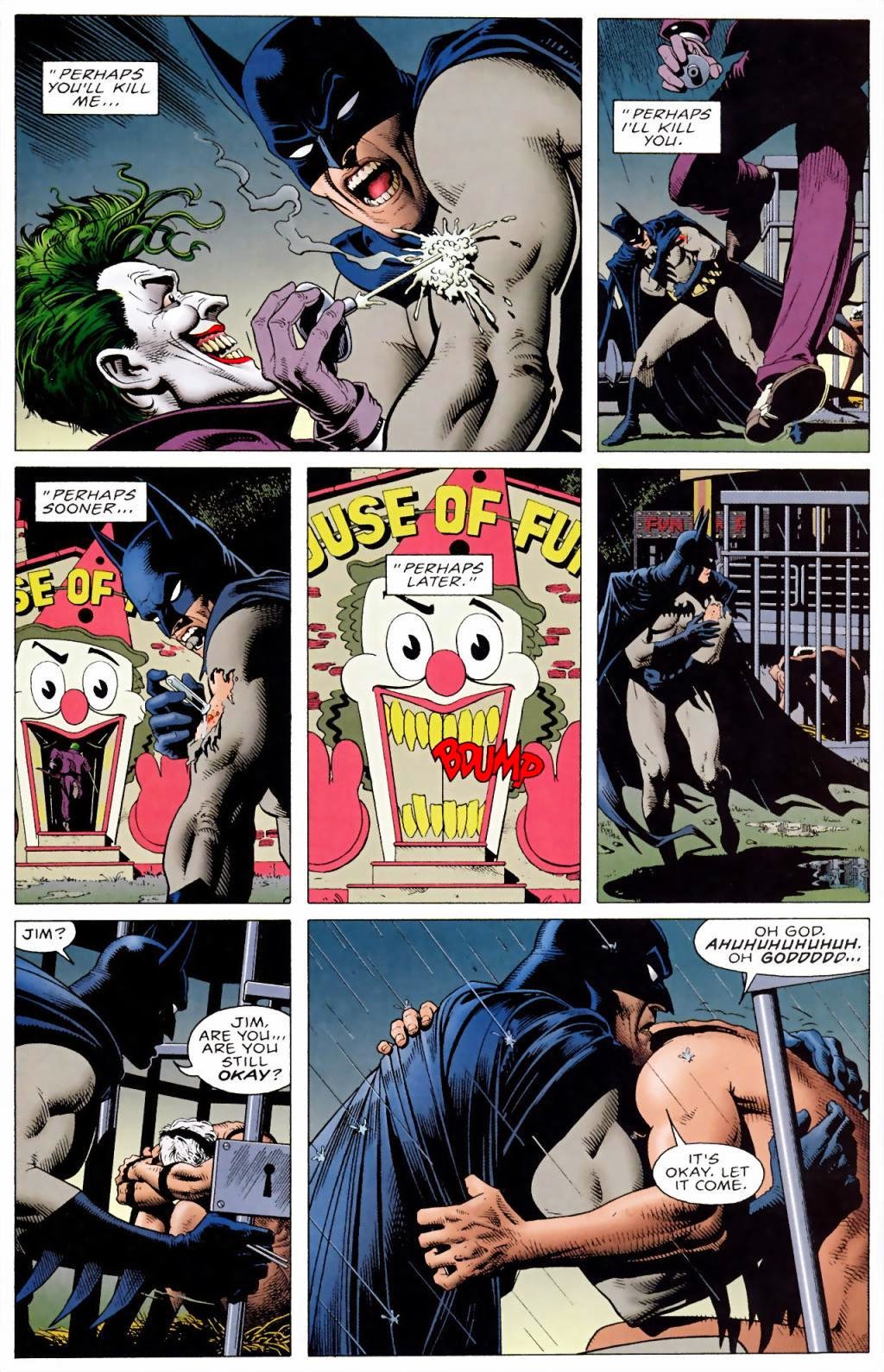

The story portrayed in The Killing Joke takes place in "one bad day". The Joker has escaped from prison. He has shot Barbara Gordon and kidnapped her father, police commissioner Jim Gordon. The infamous Clown Prince of Crime then concocts a plan to drive the commissioner, and the Caped Crusader, into madness. Batman must race to subdue the Joker and find out what's driving him before the madman bends Gordon into insanity, while, of course, maintaining his own sanity. The only question remains, is the Batman certain enough in his moral code to defeat the criminal once and for all?

The Immortal Joker

Having read my first Batman story in 2014, my first reaction was to compare The Killing Joke with the second installment of the Nolan trilogy, The Dark Knight, which includes the Joker as Batman's main opponent who victimizes a city for unknown purposes. Any Batman nerd could probably tell you this, but what I didn't know until months ago, before reading this story by Alan Moore, was that Heath Ledger, who played the Joker in The Dark Knight, read The Killing Joke as inspiration and insight for his role. What I didn't realize until after I read the book, was the story itself carried a lot of thematic and dialogue similarities with the 2008 movie adaptation.

The obvious theme, consistent in both the 2008 and 1988 Batman epics is that the only sanity in a meaningless world is insanity. The Killing Joke is thick with the finger-twitching suspense that only a motiveless, narcissistic psychopath could generate, but this was not achieved with the visual stimulation of Pfft, Baff and Pow, but with the Joker's sly, sadistic discourse on the method in his madness (kudos to Hamlet). In a scene during the The Dark Knight, while being accompanied by a mob boss and his gang, admiring the mound of cash retrieved after a robbery, the Joker lights a match and torches half the pile (still an incredible amount). The mob boss, stunned and angered, cannot accept this, but the Joker stabs back with the line "It isn't about money. It's about sending a message. Everything burns!" This almost precisely echoes the exchange which takes place in the beginning of The Killing Joke, where the Joker, having just broken out of prison, attacks Barbara Gordon, shooting a bullet through her spine, paralyzing her from the waste down. In her pain and fear and confusion, she desperately inquires of the lunatic, "Why are you doing this?" And just as in The Dark Knight scene, the Joker responds simply, "To prove a point." Now what that point is exactly, the reader doesn't discover until the end, but until then is forced onto a roller coaster ride (literally) with Jim Gordon who is thrust into a process of sick, psychological torture, which the Joker deems as a journey into true sanity. While torturing the innocent commissioner, he gives a chilling monologue, which begins, "...When you find yourself locked onto an unpleasant train of thought, heading for the places in your past where the screaming is unbearable, remember there's always madness. Madness is the emergency exit." He then prods the mind into a transitional phase of philosophy, where rationality gradually becomes the menace, and insanity the guardian angel - where reality shape-shifts. "We aren't contractually tied down to rationality!" The more I read, the more it seemed to me that this Joker figure is the quintessential representation of the dark edge of relativistic thinking, even postmodernism. Driven by a clouded, dark, tragic past, the Joker decides that life and humanity is "mad, random and pointless" and from there, purpose and morality are futile in a truly lawless, meaningless world. For the reader, this could be interpreted to even have been the Joker's escape from the mental trauma of his past's "random injustice", though the Joker is really unsure of his past. Thus, for Batman, the challenge is not just physical, but mental as he must contend for the intrinsic value of human life, the existence of meaning, and the reality of moral absolutes. And in the final battle between the villain and the protagonist, the reader finally discovers the point the Joker is trying to make, and prove, which strikingly parallels The Dark Knight. He says, about the victimized commissioner, "All it takes is one bad day to reduce the sanest man alive to lunacy." Again, incredibly similar to Heath Ledger's line, "I took Gotham's white knight and I brought him down to our level. It wasn't hard. You see, madness, as you know, is like gravity. All it takes is a little push!" This of course, was the case for the Joker himself, as is revealed in the story. The reader is given the hint that Batman had not too different an origin. The difference between the Joker and Batman - the ultimate difference between a villain and a hero - was that Batman decided to accept the unfairness of life and fight for the good that does exist, rather than flee from reality and circumstance altogether. Instead of pretending that life is "multiple choice", he sees and acknowledges the hope that exists in good. In the end, though, after inevitable defeat, the Joker realizes his guilt. He recognized that for targeting the innocent, he deserved retribution. It's in the moment where the Joker is weakest, guiltiest, and in utter defeat that the greatest quality in any hero is shown in Batman: mercy. No matter how far off a life has drifted, he recognizes the value in life and decides not to assault the assailant. I would not comment on the rather ambiguous end to this great tale, except that the ending is part of the story. Perhaps what I will say to those who'd like to read The Killing Joke is... prepare for Inception all over again. Not necessarily a bad thing.

Now I'd like to take a break from the thematic and discuss the art, though the two are not necessarily unrelated. Brian Bolland's artwork, though not overly spectacular or particularly innovative, certainly does the trick of visualizing the plot and effectively bringing out the reader's curiosity in the Joker. In fact, the visual portrayal of the Joker, himself, is as it ought to be: frightening and sinister, yet not so unearthly that he is beyond our pity. Brian Bolland is evidently generous to the audience as he allows it to not only despise the green-haired, face-painted, knife-bearing Joker character, but relate to him as well, making him a character we want to see destroyed, but also preserved simultaneously. This kind of artistic generosity does carry through to every aspect of the comic. The transitions are clever, the colors are wonderful, and the shadow of interest looms over every panel. This goes hand-in-hand with Alan Moore's carefully and very intelligently written script. Each monologue amplifies the next. Each conversation subtly buttresses our undying support for Batman and our love-hate relationship with his chief aggressor. It's the amazing effect of purposely placed words that makes this comic what it is: one of the best-selling and most popular comics ever.

The Verdict

This fantastic story about Batman and his ultimate villain, the Joker, is one that will stick with me for a long, long time, one that I will lend to my future offspring, because The Killing Joke speaks to the meaning of existence and what it means to be human. It poses a warning about the dangers of a world without absolute meaning or morality, where human life is nothing more than a bundle of atoms and energy, where life itself is mad, random, and pointless. This story serves as a great reminder to me that I am profoundly blessed to know a God who, in his love and grace, has given humanity intrinsic, sacred value. This story, moreover, reminds me, in all its powerful creativity, that true sanity is not in madness, but in worship of the One who made a way for the salvation of all from our sinful, human nature. For the themes and creative aspects that reaffirm my deepest beliefs and convictions, and the overall wonderful display of artistry and storytelling by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland, I will give this, Batman: The Killing Joke, a bold 5 out of 5. This is a genuinely classic story that I recommend, at the very least, to every young person, comic-reader or not. It'll be worth every minute of your time! -NC

The dark knight. Dir. Christopher Nolan. Warner Home Video, 2008. DVD.

Moore, Alan, and Brian Bolland. Batman: the killing joke. Deluxe ed. New York: DC Comics, 2008. Print.